Northumbrian Water

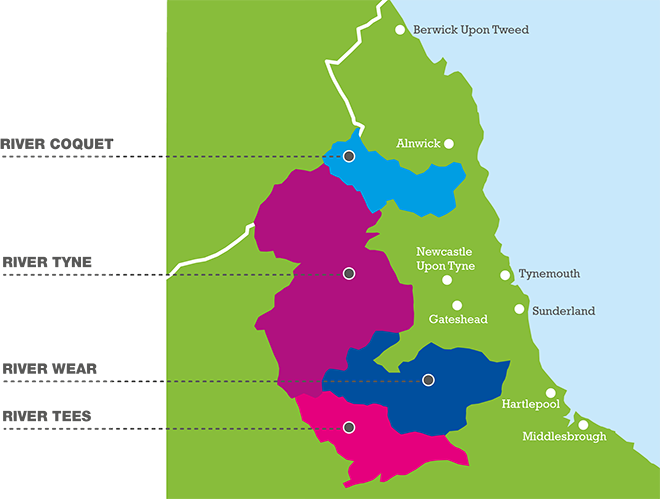

The River Coquet is around 40 miles in length and flows through the county of Northumberland. It rises in the Cheviot Hills and follows a winding course, generally eastwards to where it meets the North Sea at Amble.

The Coquet has a catchment area of just over 600km2. At its source the landscape is remote and sparsely populated. Extensive areas of blanket bog and heather moorland cover the area which is managed for grouse and grazed by sheep. The steep, lower slopes also support some beef cattle and there are extensive areas of coniferous forestry plantations. Heading east, mixed farming dominates the landscape with pasture for livestock and silage, and some arable cultivation. Heather cover dominates, providing rough grazing for sheep and habitat for grouse management. Down the slopes, there is semi-improved and rough grassland supporting extensive stock rearing, including beef cattle.

Downstream the farming becomes more intensive with large areas of improved pasture for sheep and cattle grazing, which eventually gives way to the coastal plain of North Northumberland where mixed arable, particularly cereals dominate. The river water is abstracted for drinking water supply on the outskirts of Warkworth, at the river’s tidal limit.

River water quality

The water quality of the River Coquet is generally very good and of high ecological and conservation value, designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). However, some reaches are suffering from lower quality attributed to diffuse water pollution from agriculture (DWPA). Several stretches on the main river between the Wreigh and Swarland Burns are at risk of sedimentation due to overgrazing, bank erosion and poaching. The Wreigh, Tyelaw and Thirston Burns contain elevated levels of phosphates and nitrates which is attributable to agricultural activity. The pesticide metaldehyde, the active ingredient in slug pellets, is also found in the river water. Removing these substances requires additional chemicals and energy, and can therefore increase the cost of treating drinking water.

Partnership

We work collaboratively with Natural England’s Catchment Sensitive Farming (CSF) project, as well as other stakeholders within the Coquet catchment, including farmers and landowners, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticide, nitrate, phosphate and sediment, running off the land into the river.

Events, training and advice

Alongside CSF, we host events, training and advice days on a range of topics and can provide free one-to-one farm visits to give advice on fertiliser and pesticide handling and management, sprayer and pellet spreader calibration, biobed installations and agri-environment schemes.

The River Tees rises on the eastern slope of Cross Fell in the upper Teesdale region of the North Pennine Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). It is 85 miles in length, has a catchment area of 1834km2 and flows generally eastwards to meet the North Sea between Hartlepool and Redcar.

Numerous hills surround the river’s source, some exceeding 2500ft, and the landscape is bleak with large expanses of blanket bog and heather moorland. The head of the Tees is dammed to form Cow Green Reservoir, our highest reservoir at an altitude of 480m. The reservoir is used to make regulatory releases into the River Tees to allow abstraction to take place downstream, where the landscape becomes more hospitable opening out into green dales. Here agriculture dominates; predominantly pasture for beef and sheep rearing with arable in the more fertile lowlands. The Tees flows through a number of towns and villages before it reaches our abstraction point at Broken Scar Water Treatment Works on the western edge of Darlington. The Tees has a number of major tributaries including the Rivers Lune and Balder, both of which have been dammed to create a series of reservoirs which supply our Lartington Water Treatment Works.

River water quality

A vast area of the upper Tees catchment is blanket bog. Like many peatlands, drainage channels known as ‘grips’ were historically dug to improve drainage and make the land more suitable for sheep grazing. However, this has resulted in the water draining from the uplands being a tea-like colour, caused by dissolved organic carbon (DOC), which leaches from the peat. Furthermore, the increased drainage has lead to the peat drying out and being eroded by the weather, resulting in even more DOC being carried off the land and into the river. The DOC must be removed by the water treatment process, which is costly and produces a large amount of sludge that must itself be treated and disposed of.

The Tees Water Colour Project

The Tees Water Colour Project was set up in 2005 and aimed to reduce water colour in the River Tees by focusing on management of the upstream catchment, none of which Northumbrian Water owns. Blocking the grips was seen to be the solution to reducing the leaching of colour from the bogs. In order to block the grips, we needed to work with all stakeholders including landowners and managers, the Environment Agency, Natural England, Defra, RSPB and the North Pennines AONB Partnership. The first grip was blocked in 2008, with 68km of moorland grips being instated in total.

Monitoring has been carried out by Durham University and a decrease in the amount of DOC leaching from the blocked grips compared to the remaining unblocked grips has been shown. The grip blocking had the additional benefit of restoring 196ha of SSSI blanket bog, which is particularly important as a habitat for wildlife and may play a role in flood control and as a carbon store, which if lost would contribute to climate change severity.

Monitoring continues and it may be several years before the true success of the project can be quantified.

Partnership

We work with the relevant stakeholders in the catchment, including the Tees Rivers Trust, Natural England, the Environment Agency, local farmers and landowners. We have maintained an ongoing partnership with the North Pennines AONB Partnership, supporting their work to restore the eroded areas blanket bog in the Tees catchment.

Your catchment advisor

Rob Cooper is Northumbrian Water’s Catchment Adviser for the River Tees. Rob has a First Class Honours degree in Countryside Management from Aberystwyth University. He has worked on a number of farms whilst at university; and upon graduation worked as a research assistant for the university on a number of Defra research projects, looking at biodiversity and ecosystem services. Following this, Rob worked in a number of roles for the Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG) in the East of England, including as Norfolk and Suffolk coordinator for the Campaign for the Farmed Environment (CFE).

The River Tyne is formed by the confluence of the Rivers North and South Tyne, which meet near Hexham at Warden Rock.

The North Tyne is formed from the confluence of the Kielder and Deadwater Burns which rise on the Scottish Boarders. The burns meet just north of, and then flow into Bakethin Reservoir, which in turn flows into Kielder Water Reservoir, Europe’s largest manmade water body. Kielder Water is also fed by a number of other burns, notable the Lewis Burn which drains a large area on the western side of the reservoir. Kielder Water is surrounded by Kielder forest, a primarily of coniferous woodland and the largest planted forest in Europe. The upper reaches of the catchment consists of a mixture of heather, rough grasslands and blanket bog. Flow in the North Tyne is maintained by regulated releases from Kielder Water, and flows on into more productive agricultural land with pasture on the floodplain and rough grazing on higher ground. The nature of this catchment limits the farming to livestock rearing, primarily sheep and herds of suckler cows, and is sparsely populated. The North Tyne has many tributaries including The River Rede and numerous burns of varying sizes.

The South Tyne rises on Alston Moor in Cumbria which lies in the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The area is characterised by expansive moorland with large areas of blanket bog in the upper reaches with traditional hay meadows on the lower valley slopes and some ancient woodland. The area is rich in minerals and as such has been heavily influenced by mining, particularly for lead. Downstream, traditional pasture gives way to more mixed and arable farming. Arable agriculture dominates the floodplain whilst semi-improved pasture and mixed woodland is found on the slopes. The South Tyne has a number of tributaries including the River Allen and River Nent and numerous burns.

Once the two rivers meet to form the River Tyne, the flow continues generally eastwards to meet the North Sea at Tynemouth. Along this section of the river the floodplain is dominated by large arable fields and intensively grazed pasture. We abstract for drinking water supply just to the east of Ovingham but water from the Tyne can also be sent to our more southern operating area via the Tyne-Tees transfer system.

The Whittle Dene reservoir system also sits within the River Tyne catchment and can supply both Whittle Dene and Horsley Water Treatment Works. It consists of a series of reservoirs linked by an aqueduct system of pipes, tunnels and open channels.

River water quality

Given the agricultural nature of much of the Tyne catchment there is a risk of diffuse water pollution from agriculture (DWPA). Historically, a number of pesticides have been found in the raw water at our Horsley and Whittle Dene Water Treatment Works, including metaldehyde, the active ingredient in slug pellets. Removing these substances requires additional chemicals and energy, and can therefore increase the cost of treating drinking water.

Partnership

We work with all relevant stakeholders in the catchment, including Tyne Rivers Trust, Natural England, the Environment Agency, local farmers and landowners, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticide, nitrate, phosphate and sediment running off the land and into the river.

Events, training and advice

We offer free training, advice and one to one farm visits on a range of topics, such as fertiliser and pesticide handling and management, sprayer and pellet spreader calibration, biobed installations and agri-environment schemes.

The River Wear rises in the east Pennines and is formed at Wearhead from the confluence of Killhope Burn and Burnhope Burn. Before the two meet, Burnhope Burn has been dammed to form Burnhope Reservoir.

The Wear has a catchment area of just over 1080km2 and has a number of large tributaries including the River Browney and the River Gaunless. At its source the landscape is dominated by blanket bog, heather and grass moorland and is shaped by hill farming and management for grouse. As the river heads east the land is mostly in agricultural use, sheep and upland cattle rearing in the west moving into mixed arable farming in the east. The landscape is heavily influenced by its industrial and mining past and while most of the mines are now redundant, some industry remains in the lower reaches of the catchment. The Wear flows through a number of urban areas including the city of Durham before it reaches our abstraction for Lumley water treatment works just outside Chester-le-Street.

River water quality

Historically water quality in the River Wear has been quite low due to the impacts of urban and industrial pollution but it has significantly improved over the last few decades. This is partly due to the decline in the coal industry although its legacy is still seen in the river water quality.

Parts of the Wear suffer from excessive aquatic plant growth due to nutrient enrichment from sources such as agriculture and treated sewage effluent, and as a result parts of the catchment are designated as Nitrate Vulnerable Zones (NVZs). The pesticide metaldehyde, the active ingredient in slug pellets, is also found in the river water. Removing these substances requires additional chemicals and energy, and can therefore increase the cost of treating drinking water.

Partnership

We work with all relevant stakeholders in the catchment, including the Wear Rivers Trust, Peatscapes, Natural England, the Environment Agency, local farmers and landowners, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticide, nitrate, phosphate and sediment running off the land and into the river.

Events, training and advice

We offer free training, advice and one to one farm visits on a range of topics, such as fertiliser and pesticide handling and management, sprayer and pellet spreader calibration, biobed installations and agri-environment schemes.

Your catchment advisor

Rob Cooper is Northumbrian Water’s Catchment Adviser for the River Wear. Rob has a First Class Honours degree in Countryside Management from Aberystwyth University. He has worked on a number of farms whilst at university; and upon graduation worked as a research assistant for the university on a number of Defra research projects, looking at biodiversity and ecosystem services. Following this, Rob worked in a number of roles for the Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG) in the East of England, including as Norfolk and Suffolk coordinator for the Campaign for the Farmed Environment (CFE).

Essex & Suffolk Water

The River Bure rises near Melton Constable, in central north Norfolk and meanders southwest through the Norfolk countryside to Coltishall where it joins the navigable part of the Broads.

The river continues through Wroxham and eventually meets the River Yar at Great Yarmouth, where it flows to the North Sea. The catchment comprises some 340 Km2 of mainly arable farmland. The landscape is generally flat with a soil type that is medium. The river itself is largely bordered by grassland floodplain, but there are many smaller tributaries to the main river, which reach far into the surrounding, intensively farmed, arable land.

The Trinity Broads are located close to the northeast coast of Norfolk and comprise of five interconnected Broads called Ormesby Broad, Rollesby Broad, Ormesby Little Broad, Lily Broad and Filby Broad. The Trinity Broads drain southeast to the River Bure at Acle but are disconnected from the Broads navigation area. The catchment area is some 38 Km2 of intensively farmed arable land with small pockets of grassland and grazing marsh.

The majority of these Broads are surrounded by reedbed and woodland but in some places the farmed land is within five meters of the water’s edge. Dykes draining the catchment to the Broads reach far into the surrounding farmland and villages.

River and Broad water quality

Nitrate and the pesticide metaldehyde can be present in the river water and are extremely difficult to remove through the treatment process. These substances mostly originate from agricultural land where they are applied as fertiliser, and to prevent damage to crops by slugs. Phosphate and sediment also coming from the land can result in poorer river water quality. Removing these substances from the river water requires additional amounts of chemicals and energy, and therefore increases the cost of producing drinking water.

The Trinity Broads have suffered from high nitrate and phosphate input causing algal blooms and poor water quality in the past. Catchment work and a biomanipulation project have improved water quality significantly, leading to clear water and a rich aquatic habitat. Biomanipulation is the adjustment of the fish populations allowing waterfleas, that eat algae, to proliferate, causing clear water conditions. This work is a significant success story for Essex & Suffolk Water.

Partnership

In the Bure catchment, Essex & Suffolk Water works collaboratively with Natural England’s Catchment Sensitive Farming (CSF) project and other stakeholders, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticides and nitrates, and also phosphate and sediments, running off the land into the river.

In the Trinity Broads catchment, work is being carried out with the Trinity Broads Partnership which comprises Norfolk Wildlife Trust, Natural England, the Environment Agency, the Broads Authority and Essex & Suffolk Water, and through liaison with local farmers, parish councils and leisure groups who use the Trinity Broads for recreation and business purposes.

Events, training and advice

Essex & Suffolk Water, alongside CSF, host events, training and advice days on a range of topics such as soil review workshops, biobed demonstrations, and Nitrate Vulnerable Zone workshops. We can provide free one-to-one farm visits on a variety of issues, and advice on fertiliser sprayer and pellet spreader calibration, manure sampling and analysis, biobed installations, farm mapping and agri-environment visits.

Your catchment advisor

Ian Skinner is Essex & Suffolk Water’s Catchment Advisor for the River Bure and Trinity Broads, and also for the River Waveney, Fritton and Lound Lakes. Ian has a degree in Agriculture from Newcastle University and an MSc. in Agriculture, Environment and Development from the University of East Anglia. He has worked as a contractor and relief cowman on many arable and dairy farms in Norfolk and Suffolk. He spent 15 years with the Environment Agency working with farmers to improve water quality through the NVZ Regulations and was a technical advisor for the launch of the Catchment Sensitive Farming Initiative. Ian joined Essex & Suffolk Water in 2015 to continue working with landowners in the catchments that supply our drinking water.

The Rivers Chelmer and Blackwater both rise in and flow through the county of Essex. The River Chelmer rises near Thaxted and flows mainly southeast towards Chelmsford, where it is joined by the River Can. It meets the River Blackwater at Langford near Maldon where it flows to the North Sea.

The River Blackwater rises in northwest Essex as the River Pant. It flows through Braintree and is joined by the River Brain before flowing towards Maldon and out to the North Sea via the Heybridge Basin or the tidal Chelmer.

The Chelmer & Blackwater catchment is 988 Km2 and is intensively farmed for predominantly arable crops, with a small amount of livestock. The landscape is gently rolling with a soil type of mainly loams and clays.

River water quality

Nitrate, and the pesticides clopyralid and metaldehyde can be present in the river water and are extremely difficult to remove through the treatment process. These substances mostly originate from agricultural land where they are applied as fertiliser, and to prevent weed growth and damage to crops by slugs. Phosphate and sediment also coming from the land can result in poorer river water quality. Removing these substances from the river water requires additional amounts of chemicals and energy, and therefore increases the cost of producing drinking water.

Partnership

Essex & Suffolk Water is a member of the Chelmer & Blackwater Strategic Partnership, along with the Environment Agency and Natural England’s Catchment Sensitive Farming (CSF) project. The Partnership works closely with Campaign for the Farmed Environment (CFE), National Farmers Union (NFU), Association of Rivers Trusts, farmers, land managers and agronomists, among others, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticides, nitrates, and also phosphate and sediments, running off the land into the rivers.

Events, training and advice

The Partnership hosts events, training and advice days on a range of topics and can provide free on-farm one-to-one fertiliser sprayer and pellet spreader calibrations, farm health checks, farm mapping and agri-environment visits.

Your catchment advisor

Thomas Harris is Essex & Suffolk Water’s Catchment Advisor for the Chelmer and Blackwater. Having worked on farms in Essex and beyond from the age of 14, he has a good practical grounding of both the positive and negative aspects of farming in the catchment. In addition Tom has spent a total of 6 years studying Agriculture at Writtle University and has gained around 4 years working in crop trials for a large distribution company.

For much of its 45 mile length, the River Stour marks the county boundary between Essex and Suffolk. Rising in Wratting Common in Cambridgeshire, the river runs in a south-easterly direction, discharging into the North Sea just north of Manningtree. The River Stour has 7 major tributaries including the rivers Glem, Box, Brett, Stour Brook and Chad Brook.

The Stour catchment is 858 km2 and is intensively farmed for predominantly arable crops, with a small amount of livestock. The landscape is undulating with a soil type that is mainly chalky clay.

River water quality

Nitrate, and the pesticides clopyralid and metaldehyde can be present in the river water and are extremely difficult to remove through the treatment process. These substances mostly originate from agricultural land where they are applied as fertiliser, and to prevent weed growth and damage to crops by slugs. Phosphate and sediment also coming from the land can result in poorer river water quality. Removing these substances from the river water requires additional amounts of chemicals and energy, and therefore increases the cost of producing drinking water.

Partnership

Essex & Suffolk Water works collaboratively with Natural England’s Catchment Sensitive Farming (CSF) project, as well as other stakeholders within the Stour catchment, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticides, nitrates, and also phosphate and sediments, running off the land into the river.

Events, training and advice

Essex & Suffolk Water, alongside CSF, host events, training and advice days on a range of topics and can provide free one-to-one farm visits on a variety of issues, advice on fertiliser sprayer and pellet spreader calibration, biobed installations, farm mapping and agri-environment visits.

Your catchment advisor

Steve Derbyshire is Essex & Suffolk Water’s Catchment Advisor for the Stour catchment. Steve has a strong agricultural background with an HND and BSc in Agriculture, and is BASIS and FACTS qualified. Steve has previously worked for an independent research company conducting agricultural chemical trials, and he has worked on farms in the UK and overseas, gaining an in-depth knowledge of pesticide use in agriculture.

The River Waveney rises just east of Diss and marks the county boundary between Norfolk and Suffolk. The river flows northeast through Beccles and Bungay where it joins the Broads navigation area, and then on to meet the River Yare at Great Yarmouth, where it enters the North Sea.

The catchment comprises 666 Km2 of mainly arable farmland on mainly medium soils. The river is boarded by grassland floodplains for the majority of its length but its many tributaries, including the River Dove, reach far into the surrounding, intensively farmed arable land.

The Lound Lakes, which includes Fritton Lake, are located on the boarder between Norfolk and Suffolk, between Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft. The lakes are a linear series of manmade basins, draining west to the River Waveney at St Olaves. The lakes were historically formed from peat diggings and then later utilised for their water storage. The catchment is 20km2 of intensively farmed arable land with a small amount of livestock.

River water quality

Nitrate and the pesticide metaldehyde can be present in the river water and are extremely difficult to remove through the treatment process. These substances mostly originate from agricultural land where they are applied as fertiliser and to prevent damage to crops by slugs. Phosphate and sediment also coming from the land can result in poorer river water quality. Removing these substances from the river water requires additional amounts of chemicals and energy, and therefore increases the cost of producing drinking water. The Lound lakes principally suffer from high inputs of nitrate and phosphate from the catchment, which leads to algal blooms and poor water quality.

Partnership

In the Waveney catchment, Essex & Suffolk Water works collaboratively with Natural England’s Catchment Sensitive Farming (CSF) project and other stakeholders, through the River Waveney Catchment Partnership, with the aim of reducing the amount of pesticides, nitrates, and also phosphate and sediments, running off the land into the river.

In the Lound lakes catchment, work is being carried out in partnership with Natural England, the Environment Agency and the Broads Authority, and also with the Somerleyton Estate who own Fritton Lake, and with other land owners and tenants in the catchment.

Events, training and advice

Essex & Suffolk Water, alongside CSF, host events, training and advice days on a range of topics such as soil review workshops, biobed demonstrations, and Nitrate Vulnerable Zone workshops. We can provide free one-to-one farm visits on a variety of issues, and advice on fertiliser sprayer and pellet spreader calibration, manure sampling and analysis, biobed installations, farm mapping and agri-environment visits.

Your catchment advisor

Ian Skinner is Essex & Suffolk Water’s Catchment Advisor for the River Waveney, Fritton and Lound Lakes, and also for the River Bure and Trinity Broads. Ian has a degree in Agriculture from Newcastle University and an MSc. in Agriculture, Environment and Development from the University of East Anglia. He has worked as a contractor and relief cowman on many arable and dairy farms in Norfolk and Suffolk. He spent 15 years with the Environment Agency working with farmers to improve water quality through the NVZ Regulations and was a technical advisor for the launch of the Catchment Sensitive Farming Initiative. Ian joined Essex & Suffolk Water in 2015 to continue working with landowners in the catchments that supply our drinking water.